From my previous postings, it may be clear that I have an interest, even a fascination, with the ongoing discussions of job creation by people in positions of leadership about job creation. I posted a question on LinkedIn last week asking how many of our senators and representatives in

Washington, DC have a background suggesting experience in creating jobs. I raised the question because evidence indicating such experience seems thin after more than two years of conversation about economic recovery and the need to reduce unemployment through job creation.

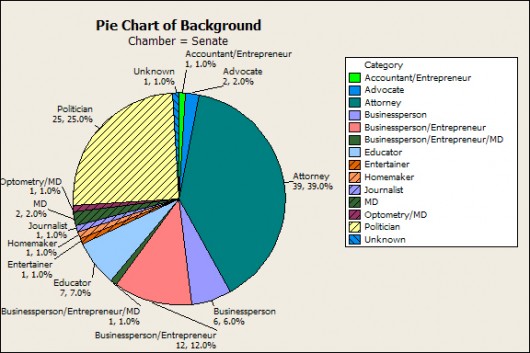

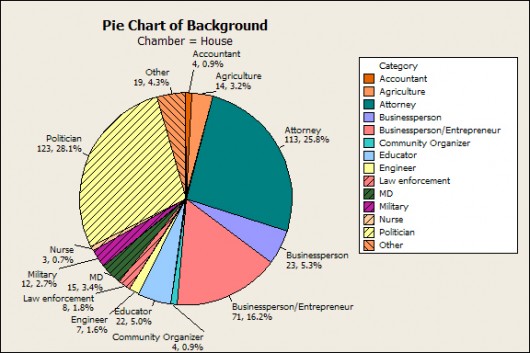

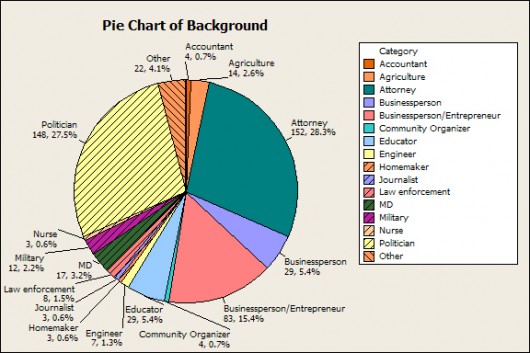

Since several people responded that I raised a good question and nobody seemed able to answer the question, I spent part of my 4th of July weekend reviewing the biographies of each member of the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate, as found at house.gov and senate.gov. The chart below shows the combined number from both chambers.

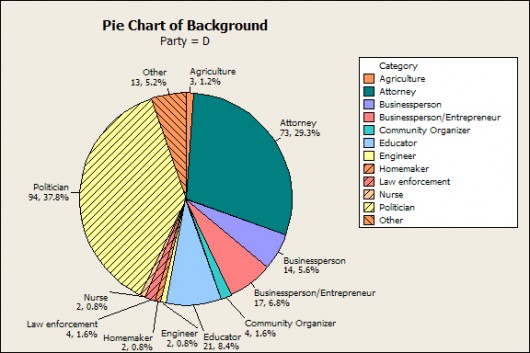

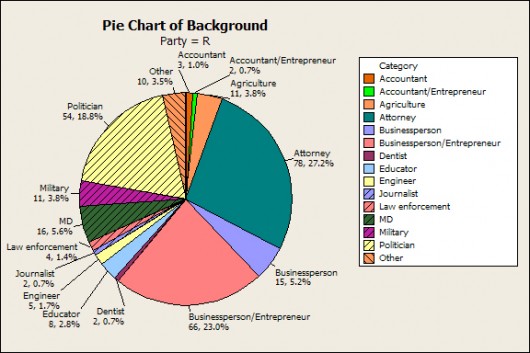

In these charts, I use the term “politician” to mean anybody whose indicated background includes only positions involved in negotiating and defining public policy or having no experience other than in those positions since 1980. I use the term “entrepreneur” to mean experience owning, building, or starting a small business.

The data shows that 300 of 538 current officeholders in the House and Senate are almost equally divided between politicians and attorneys. 111 of our national legislators were businesspeople or entrepreneurs prior to election to public service and five more were accountants (one of which was also an entrepreneur); among the “Other” is one senator who was both a physician and an entrepreneur. Twenty were either physicians or nurses with two among the “Other” identified as dentists and one each of the “Other” an optometrist, a scientist, and a psychologist. Twenty-nine educators, eight engineers (one of which was also an entrepreneur), fourteen farmers, twelve members of the military, eight members of the law enforcement community, four community organizers, three homemakers, and three journalists round out the remaining non-“Other” legislators. The “Other” include a football player, ordained ministers, community organizers, communications professionals and journalists, an entertainer, a health administrator, an ironworker and a millworker.

My research on leadership suggests that our culture shapes our perception of appropriate roles, practices, and behaviors of leaders. My research also seems to indicate that the roles that we fill or play in life shapes our individual interpretations of culture, which itself reflects or defines our norms and values, and, therefore, influences how we view the world and how we lead in it. We can expect, therefore, that

politicians view the world differently from attorneys who view the world differently from farmers and businesspeople and accountants and ministers.

It seems that the question we should ask ourselves, before we cast our votes, is does this person have the worldview and the background necessary to solve our problems and do we need people to develop solutions or are we better served by people whose background is in policy or in law? I realize that the problems of today are not necessarily the problems of yesterday or of tomorrow, but would we be better served by staff who know how to write policy and legislators who know how to fix things and make things work? It appears that, when job creation and economic recovery is essential, we have too few elected leaders who have ever created jobs or stimulated a local or national economy and an abundance of people who should know how to negotiate and convince and write policies and laws. Does the United States have the right leadership with the right expertise?

The following four pie charts show the breakdown for democrats and republicans and for each of the two chambers. I leave it to the reader to draw your own conclusions.