In the August 27, 2012 issue of Time, Rana Foroohar (2012) wrote about globalization. Foroohar asserted that globalization was originally all about creating a lop-sided benefit for companies and workers in the United States. On the surface, this is a rather parochial, if not absurd, concept. Foroohar, in effect, proposed that globalization’s purpose was economic colonialism, overcoming boundaries, borders, and barriers.

The Levin Institute (2012) noted that international trade both causes and results from globalization. The proliferation and distribution of products from the United States is an example of globalization as is the availability of goods and services from Japan, South Korea, China, Germany, France, Italy, and Mexico. Trade negotiations effectively negated the consequences of any intended one-sided, eco-colonialism.

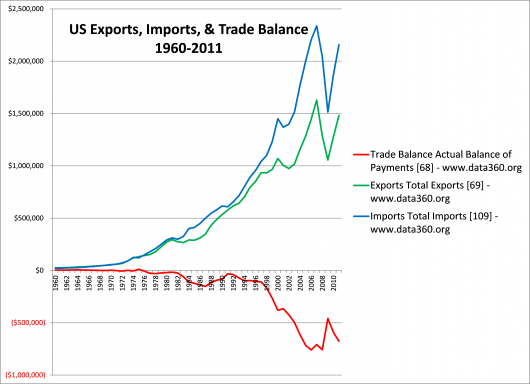

Trade negotiations did not seem to reduce either exports or imports. Despite the economic downturn that struck most of the world’s economies in 2008, imports and exports since the beginning of globalization continue their upwards march, albeit with a noticeable dip in both imports and exports in 2008 and 2009. The assertion by Foroohar (2012) that globalization harmed the wages and upward mobility of workers in the U.S. would not seem to be related to a reduction of exports, as measured in dollars. Globalization seems to have increased exports and imports.

The detrimental phenomenon related to globalization, or not, is that U.S. imports have exceeded exports every year since 1975. The steady rise in exports since 1975, only dropping briefly in 2001-2002 and 2008-2009, would seem to have enhanced wage and mobility opportunities for workers in the U.S.. Similarly, the parallel rise in imports would seem likely to have had a corresponding influence on the economic well-being of workers in the countries from which the U.S. imports goods and services. Foroohar (2012) notwithstanding, perhaps the opportunity in the U.S. is not to somehow try to put the brakes on globalization, as if the U.S. is in control of such phenomenon, but to reduce the overall trade imbalance by taking steps through policy, innovation, and better management. Slowing globalization would seem to have the potential to reduce imports and exports; the objective should be to narrow or close the gap by some combination of continued growth in exports and a slowing of the growth in imports.

References

Foroohar, R. (2012, August 27). The economy’s new rules: Going global. Time, 180(8), 26-32.

The Levin Institute. (2012). Trade and globalization. Retrieved September 2, 2012 from http://www.globalization101.org/trade-introduction/